Overhaul 19b: Carrier Team One Reflections2

Introduction

In my previous post, I discussed some causes of bad overhaul performance. The short version: bad outcomes in ship repair come from continuing to do dumb stuff that would never get your RV fixed on time for a reasonable price. Why anyone thinks ship overhaul is fundamentally different from RV maintenance is beyond me. The price might even be close. There is one big difference: no one actually tries to live in their RV and criticize the mechanics while they’re working..

Following my list of ten dumb things to stop doing in ship overhaul, I described the set-up for what was later called the first Carrier Team One meeting in February 1997. It was a bold effort to identify the dumb things we were doing at the time and change the processes that produced them that took place under a church. When you try to work on institutionalized dumb things in an organization like the Navy, it is a good idea to get as close as you can to God. Maybe this is the real lesson of the Constellation class frigate design. Its program office lost a design competition with Satan.

This post isn’t a history of CT1. It’s a reflection on why that first meeting mattered — and what made it a bureaucratic anomaly worth learning from. What happened at the meeting was important because it started the Carrier Maintenance Community a path of thinking differently about maintenance process improvement.

The Remarkability of Carrier Team One

Remarkability” isn’t a word, but it should be. Plus, it is more fun to say than “remarkableness.” Remarkable is how I describe the crazy strange (my style checker hates that, but it fits here) things people did to improve carrier maintenance after CT1 leaders unleashed them.

The carrier maintenance meeting in 1997 was remarkable in many ways. In later years, one of the two organizers of the 1997 meeting referred to what CT1 sought to do as an “unnatural act.” It was unnatural because most organizations focus only on their own issues. It wasn’t common then (perhaps not even now) to view maintenance as a collection of systems where the most critical things needed to happen between organizations.

Remarkable Thing One, the meeting and its format were orchestrated by two ringleaders with big ideas and deceptively modest goals. Like Steve Jobs, they wanted to make aircraft carrier maintenance “insanely great.” Unlike Jobs, they didn’t tell anyone — or have sleek ads for it. They had been trying for over a year (unsuccessfully) to start improving carrier overhauls because an Admiral said so. Admirals direct people to do many things. Some people listen. Fewer actually try to do something.

The meeting ringleaders were assisted by the Shipyard Commanding Officer (SYCO) who sponsored the meeting. He didn’t so much sponsor the event as wisely get out of the way. You’ll never see “He knew when to get out of the way” as an attribute of a great leader on their tombstone (even though it would be super cool) or in a book about leadership. Leadership books stress involvement and other “great man” characteristics. One of the best leadership statements I ever heard was, “I don’t understand what you’re doing, but keep going, and I’ll try not to bugger it up.”

The meeting was almost canceled before it happened. That was a good thing. If senior leaders want to prevent your meeting from happening, it’s a sign that you’re on to something. That’s different from stopping someone from pushing a red, self-destruct button, which can only produce bad results. The trouble is, most senior leaders can’t tell the difference.

While employees from the sponsoring shipyard were busily collecting data and debating which ghastly problems to present at the meeting, SY Department Heads found out what they were up to. They were horrified because telling outsiders about problems at your organization, especially if they pay the bill for them, IS like pushing the self-destruct button.

The department heads were so horrified that they rapidly scheduled a meeting with the SYCO. They wanted to call project team members to account for having the audacity to report real problems to outsiders. That kind of temerity had to be stopped!

After hearing the draft presentations, the department heads recommended that the SYCO cancel the meeting. As one of them said, without a trace of irony, telling outsiders about SY problems might encourage them to help solve them! We can’t have that. In his defense, he may have seen plenty of disasters result from trying anything like that in the past.

As a reader of this blog commented to me, SY project teams are told all the time by higher authority to ask for what they need when they assess an availability as Hight Risk. When they do, the three most common outcomes are:

yelling and chair throwing when what operators want repaired costs more than their budget (try that with the RV repair guy),

lack of follow up or stonewalling by subordinates of the senior leader (who never gets informed his own people are obstructing him),

arguments from people who don’t (or never have) worked in a SY about why what the project team wanted isn’t available or isn’t really needed.

I’ve experienced all three of these.

Fortunately, the SYCO overruled his department heads. This takes fortitude or temerity. It might have been because he had just been the type commander representative and wanted to know himself.

Remarkable Thing Two, Three aircraft carrier availabilities had finished within months of each other. Two were very successful (one on each coast). One was a flaming garbage barge of lateness and expense (sound familiar?). Reporting on the performance on three availabilities performed by two SYs provided a rich collection of “things gone wrong” even for the successful projects.

Remarkable Thing Three, The meeting organizers asked the three shipyard project teams to present, with data, obstacles to their productivity. “Begged to present” is more accurate. This started with issue papers that were turned into slides because no one wants an issue paper read to them.

I participated in issue collection, analysis, and presentation for one shipyard. Being asked to present problems sounded like a license to steal! Since department heads couldn’t censor the presentations, we could complain about anything. Almost. They made it clear they’d be watching — at least on Day One.

The reality is that no organization is going to sponsor a meeting with powerful senior leaders to tell them what the sponsor’s own organization is doing badly. Nope. Confession may be good for the soul, but not in a bureaucracy!

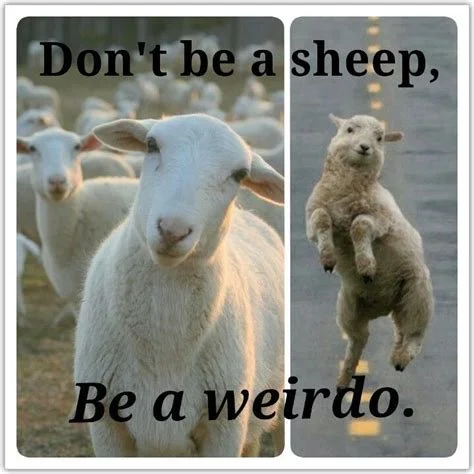

The most the sneaky organizers could hope for was that, in the midst of complaining about the dumb requirements from outside organizations, the presenters might swerve into areas where they had more degrees of freedom than they imagined. Shipyard workers get treated like sheep so often that they forget they’re not.

Remarkable Thing Four, the meeting was an open forum. There were no off-line discussions or senior-leader-only discussions. Shipyard attendees presented issues and the senior leaders discussed them with each other, out loud, in front of the attendees. Attendees were allowed to observe and participate in the conversations.

Open-forum reflection about problems is not encouraged in large organizations like the Navy. Typical post availability “lessons learned” are rote performances — theater with slides (adding Kabuki costumes would be a nice touch). They identify neither repeatable lessons nor include enough public reflection to enable learning that might facilitate doing something differently.

Lessons learned events are organized around one theme: “You SY idiots!” The safest thing for SY attendees is to present some slides on things like the need for better communications, more minute work breakdown structure (which never fixes anything), and better work package definition. Then everyone goes back to work doing what they did before. Hence the cynical nickname: “Lessons Told Meetings.”

Remarkable Thing Five, every Navy senior leader involved in carrier maintenance heard the same information at the same time. They learned in parallel. They learned from presenters and from each other very efficiently. Furthermore, they came prepared because every PowerPoint presentation was based on a point paper they read before coming to the meeting.

Remarkable Thing Six, the analysis of problems by the senior leaders was process focused. Leaders weren’t looking for “the person responsible when something goes wrong.” Most ship overhaul processes are too complex for that. GAO reports about ship overhaul delays hint at the complexity of overhaul problems by naming many that aren’t the responsibility of any single organization (like Availability Work Packages). Before CT1, no one was responsible for fixing the plumbing between the buildings — just what was happening inside them.

Remarkable Thing Seven, it became clear from the presentations and ensuing discussions that no one understood the end-to-end processes that were failing. There were plenty of metrics. That wasn’t the issue. No organization owned processes like work control or work package authorization, so there was no “person responsible” for improving them.

The senior leaders chartered Process Action Teams (PATs) to work on the most significant problems. Their first task? Map the process, define the mess, and figure out where the boundaries actually were. Process owners were tentatively assigned for each problem.

Before CT1, most overhaul processes with multiple organizations participating didn’t have owners. For example, a process fundamental to maintenance, system tagout, was governed by an OPNAV instruction. Who on the OPNAV is responsible for the technical procedures for maintenance? It’s the person who owns submarine headlight design. In a Damascene moment, meeting attendees learned that this process had no owner.

Remarkable Thing Eight, since problem investigation, meetings, and team support require people with knowledge and those people require money, the three senior leaders with budgets established a fund for expenses (salaries, travel, facilitation). They did this without proof that there would be any return on the investment. It was an act of faith something good had to come from better process knowledge. The action was also based on the realization that the sponsors could only get maintenance done in carrier shipyards, so they had an important interest in helping them be more productive. I’m not defending this as a standard practice, but it was certainly amazing.

Remarkable Thing Nine, the meeting was facilitated. Facilitation isn’t necessary for the “let’s get this over with” style of most lessons learned meetings. Because nothing controversial ever comes up in them, lessons learned meetings never are (that’s a meta lesson).

Bringing in professional facilitation made a difference. First, it prevented endless debate and kept the meeting on schedule (mostly). Second, it kept senior leaders from dominating the discussions (mostly). Third, it reduced the time wasted from speakers being “in violent agreement,” but continuing to talk ad nauseam. This is mostly a senior leader and Limited Duty Officer affliction.

Finally, it enabled rapid intervention to counter shouting and potential chair throwing. Loud voices and airborne chairs are real risks at meetings when people have strong feelings about significant problems like maintenance. If the issue you raise at a post-availability review doesn’t risk shouting, it probably doesn’t matter.

What CT1 Got Right

Carrier Team One wasn’t just unusual — it was a below-the-radar insurgency against bureaucratic entropy. The organizers created a Blame Free Zone in which they invited carrier maintainers from the two carrier repair shipyards to present bad news. The bad news took the form of processes external to the shipyards (at first) that were leading to consistently bad results (the “dumb things” list from the first post in this series).

At its core, the approach to making things better was process focused. Much later, a people development focus was added when organizations decided they needed help teaching their project team members how to become systems thinkers and use a process approach. You might think you have wonderful processes, but if your people don’t understand how to use them, it matters little.

Like quantum mechanics, people’s experience doesn’t prepare them for understanding how to think about processes and systems. Their process thinking starts with the garbage idiots upstream hand them or the impossible situation they occupy and ends just before they hand off something to the next person (who also complains about getting garbage).

Thinking in terms of systems and processes was just the start of the “thinking different” CT1 started. Systems thinking was just the beginning. CT1 didn’t stop at process — they went after people’s wiring. More on that next time.